Size

Size matters, especially for whales because they are a “capital breeder”, as opposed to the other group of mammals that are “income breeders”.

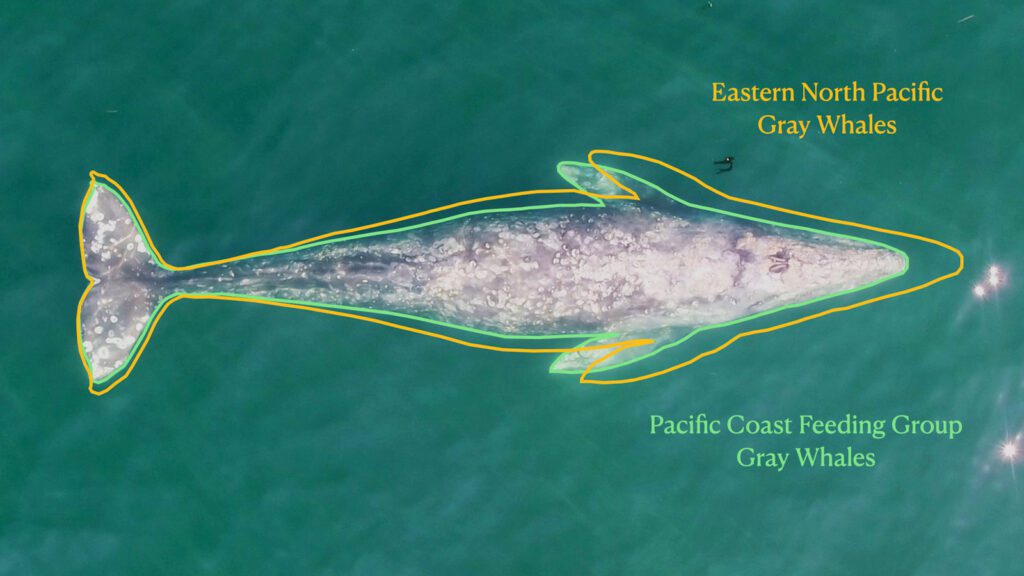

What’s even more dramatic is that these gray whales foraging in the northeast Pacific have gotten 13% shorter in the last few decades! We flew drones over the same individual gray whales for eight years, which allowed us to measure their length and determine their growth rates, finding that a whale born in 2020 would end up being about 1.65 meters (5 feet, 5 inches) shorter than a gray whale born prior to 2000. That’s a huge difference!

Want to read more? Check out these resources:

Bierlich KC, Kane A, Hildebrand L, Bird CN, Fernandez Ajo A, Stewart JD, Hewitt J, Hildebrand I, Sumich J, Torres LG (2023) Downsized: gray whales using an alternative foraging ground have smaller morphology. Biol Letters 19:20230043 doi:10.1098/rsbl.2023.0043. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/abs/10.1098/rsbl.2023.0043

Pirotta E, Bierlich K, New L, Hildebrand L, Bird CN, Fernandez Ajó A, Torres LG (2024) Modeling individual growth reveals decreasing gray whale body length and correlations with ocean climate indices at multiple scales. Global Change Biology 30:e17366 https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1111/gcb.17366

Torres, L.G., C.N. Bird, F. Rodríguez-González, F. Christiansen, L. Bejder, L. Lemos, J. Urban R, S. Swartz, A. Willoughby, J. Hewitt, and K. Bierlich, Range-Wide Comparison of Gray Whale Body Condition Reveals Contrasting Sub-Population Health Characteristics and Vulnerability to Environmental Change. Frontiers in Marine Science, 2022. 9. https://www.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmars.2022.867258

Press releases:

Blog: A smaller sized gray whale: recent publication finds PCFG whales are smaller than ENP whales https://blogs.oregonstate.edu/gemmlab/2023/11/06/a-smaller-sized-gray-whale-recent-publication-finds-pcfg-whales-are-smaller-than-enp-whales/